If either your spouse, your girlfriend, or your broker ever tell you that “size doesn’t matter” then rest assured that you are being lied to. And yes it does matter ‘how you use it’ but it comes with some caveats.

Unfortunately I can’t offer you any dating or love advice, but when it comes to trading accounts there are several reasons why size matters very much, no matter how much wishful thinking may permeate the conversation.

Position Sizing

Now a small starter account of $5,000 will of course be more than sufficient in order to buy yourself a fistful of naked options (no pun intended) or – better yet – a few vertical spreads. But position sizing and risk management will be much more tricky than trading for example with a $50,000 account.

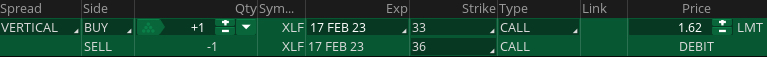

Let’s say for example XLF is currently at $34 and you want to buy an in/out vertical spread for $1.62. Don’t worry about the type of spread, the expiration, or the strikes.

Just know that it’s a simple debit spread that will cost you $162 (as one contract always controls 100 shares). There’s no margin or buying power reduction to worry about.

So far so good. Once you got your fill you’ve effectively deployed 3.24% of your trading capital on this trade. That doesn’t sound like much, does it?

Actually a position size of over 3% is considered to be fairly aggressive and especially inexperienced traders should never allocate more than 2% of their account principal to a single campaign, at least for their first year or two.

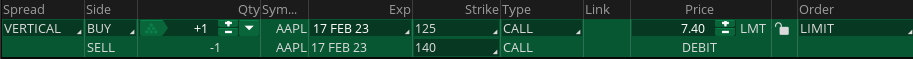

And XLF was actually quite a cheap spread compared with for example AAPL (trading at $134 at the time) where a similar I/O spread would cost you a whopping $740. And in the process eat up nearly 15% of your $5,000 trading account.

So clearly a small account principal limits the type of trades you will be able to take. And that’s a problem because skipping opportunities because of a lack of trading capital will invariably affect your trading results over the long term.

![]()

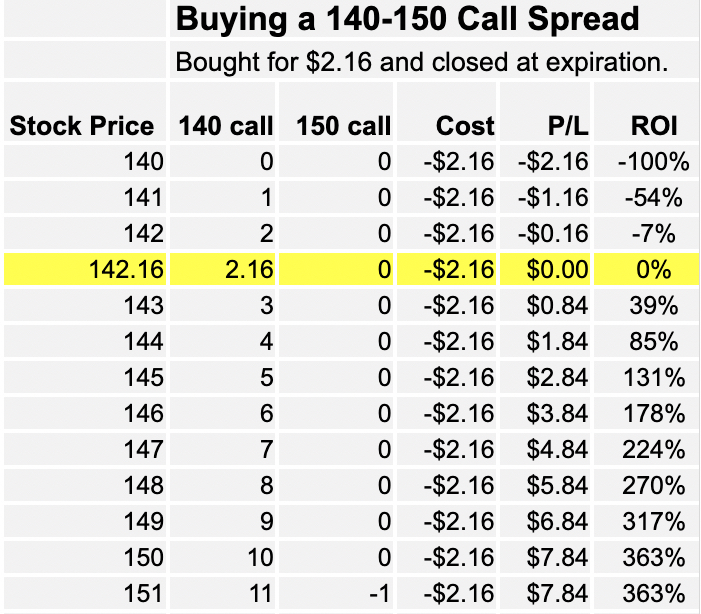

Some people compensate by taking trades they can actually afford, which in most cases means buying an out-of-the-money (OTM) option or a vertical spread. There’s nothing wrong with doing that, but of course it lowers the probability that your spread will earn you a penny or more.

As you can see, even pushing the spread out-of-the-money (OTM) by 7 handles will still produce a debit of $216, which is 4.3% of your $5,000 trading account.

Take four or five losers in a row at > 4% position sizing and a significant chunk of your account principal has gone poof. Which can easily happen when buying OTM options.

And remember, if you’re paying $2.16 for your 140/150 vertical spread then AAPL would have to push at least to $142.16 (over 8 handles higher) in order for you to reach even break/even at expiration, let alone make you any money.

And given that you paid $2.16 for a $10 spread (i.e. 150 – 140) means this spread only has a 21% chance of making you a single penny. So here you are risking over 4% of your account principal on a trade with barely a 1:5 chance of succeeding.

Not exactly an express elevator to instant riches, I would say.

Buying Power Reduction

Note that I have not even touched on margin requirements and buying power reduction. Most traders usually focus on margin but it’s really buying power reduction you should be concerned with.

You see, most people get really obsessed when it comes to margin. The Fed came up with regulation T margin way back in the 70s, which defines the minimum requirements for stocks bought on margin.

Each broker needs to abide by reg-T but they are free to stipulate whatever buying power reduction they may choose.

For your $2.16 spread your buying power reduction is simply your debit as that is the maximum loss you can ever incur. Easy-peasy lemon squeezy.

However, buying power reduction is sometimes a bit harder to quantify because it depends on the type of trade you take (defined risk v. undefined risk), the type of broker, and the type of brokerage account (margin, portfolio margin, IRA, etc.).

But let’s use an example I grifted straight off TastyTrade’s online educational site:

Example: Sell 1x 49 put for a $1.50 credit in XYZ, trading at $50.00

Here you are selling a naked OTM put with a strike price at 49. This is called an ‘undefined risk’ trade, which is fancy trader lingo for saying that this trade carries unlimited risk potential (in theory at least).

The way TastyTrade calculates your buying power requirement in this case is by using the largest product of three formulas. If you’re not into math just ignore the details and focus on the three results below:

- 20% Rule – 20% of the underlying, less the difference between the strike price and the stock price, plus the premium value, multiplied by number of contracts.

- Underlying Value: 20% x [$50.00 x (1×100)] = $1000

- OTM Amount: (49-50) x 100 = -$100

- Premium Value: $1.50 x 100 = $150

- Buying Power Requirement: $1050

- 10% Rule – 10% of the exercise value plus premium value.

- Exercise Value: 10% x [49 x (1×100)] = $490

- Premium Value: $1.50 x 100 = $150

- Buying Power Requirement: $640

- $50 Plus Premium Value – $50 multiplied by number of contracts, plus premium value.

- $50 Value: $50 x 1 contract = $50

- Premium Value: $1.50 x 100 = $150

- Buying Power Requirement: $200

In this case the 20% rule takes precedence and $1050 of your $5000 (1/5th of your account principal) in buying power reduction would be held in order to make sure you’re able to sustain the anticipated market volatility until expiration.

Which doesn’t leave you that much trading capital for taking other positions. Now if you traded with a $50,000 account and took the same entry then a buying power requirement of $1050 would only represent 2% of your account principal, which isn’t much to worry about.

There are other reasons why trading capital matters very much and most of it relates to institutional and professional traders who are able to hedge their open positions by buying or selling futures contracts like the E-Mini or even take on large holdings of stocks.

In most cases that is not a possibility for small account holders due to a lack of liquidity or sophistication. Of course that doesn’t mean trading with a retail account is a bad thing or that only institutional traders get all the perks.

In fact smaller accounts allow you to be a lot more nimble and often enable you to get in and out of your positions much quicker than someone who’s trading hundreds of contracts and has to worry about affecting price when taking on or dumping their positions.

But there are certain base requirements when it comes to trading – and obviously also when trading options, which usually is considered to offer high leverage for relatively low investment.

In general I recommend a minimum of $5,000 for buying naked options or spreads, and a minimum of $20,000 in capital when it comes to selling them.

Yes, it’s possible to start out with less, but in that case the immediate focus should dbe on compounding and on adding additional funds to your trading account over time.

Consider trading as a vehicle and your trading capital as the fuel. The more fuel you have to burn the further you are able to go. Unless of course you toss in a match and blow it all up 😉

Which is exactly what we are trying to keep from happening by offering quality education and basic rules that put you on the fast track to long term success and prosperity.

And that’s why you should take advantage of our 2023 kick start super sale which offers a massive discount if you sign up for Red Pill Quants Unlimited for an entire year.

Not good enough for you?

Right now on this page ONLY until tomorrow (12/31) at New Year’s Eve you can lock in LIFETIME access.

That’s right, never pay us a single cent again and enjoy our premiere options trading service for the rest of your natural (or unnatural) life.

Awesome, right? But you can only get it on this page for a few more days, so lock in those savings while my temporary insanity lasts 😉

The clock is ticking and once that deal is gone it won’t be back anytime soon.

LIVE cumulative P&L of all my trades over the past year can be found here.

You can sign up right here.

See you on the other side.